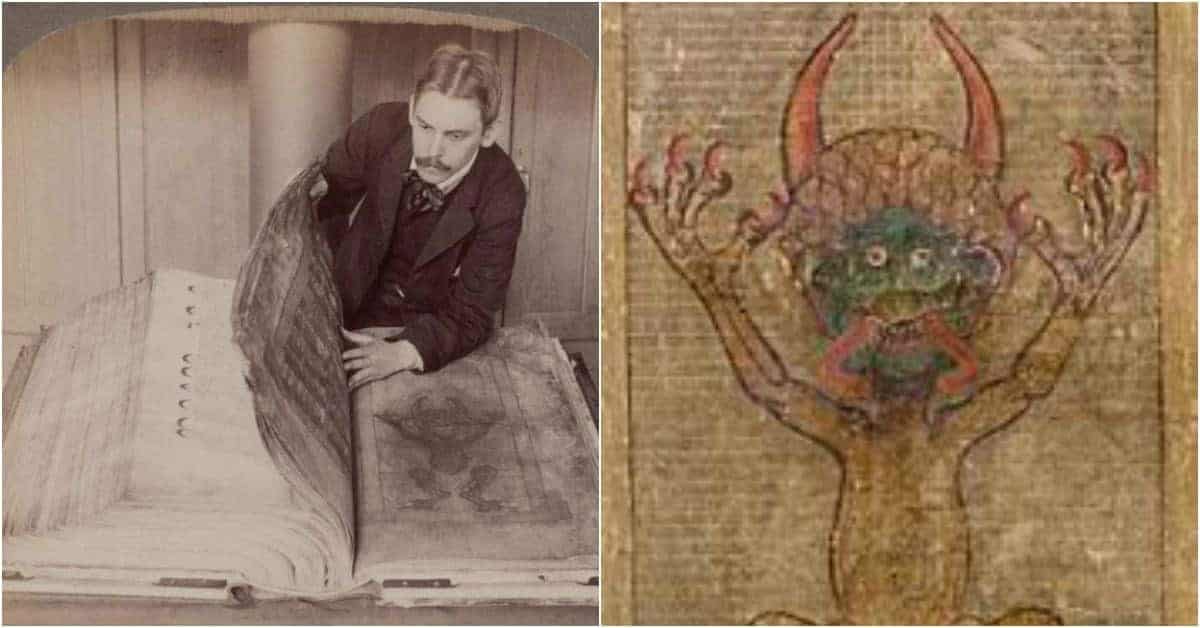

The parchment pages, the manuscript was bound. Illuminators had finished writing and decorating To the figures and vines, the illumination was finished. Once the illuminatorĪpplied black outlines, and delicate white highlights The paler shades first, then the darker tones. Each color was made from a vegetable dye, or a mineral substance, ground After applying the gold leaf, the illuminator painted his design. Then, the illuminatorīrushed away the excess, and polished the gold leaf. Small piece of gold leaf stick to the page. Illuminator's breath was enough to make the Once the gum base dried, the moisture in the Substance called gesso, or a gum, as shown here. The illuminator put down a base coat, consisting of either a plaster-like Thin sheets of precious metals, like gold leaf, were always applied first. The features of a figure, or the interlacing of a decorated initial. The illuminator first sketched his design, then added details such as He began only after a scribe had finished copying the text. The pages of a manuscript using paint and precious metals. Because the page was made from parchment, which was very resilient, it could stand many erasures of this type. If a scribe made an error, he would scratch it out with a pen knife.

Medieval scribes and their patrons prized a regular and elegant script. Before the scribe began writing, he ruled the parchment Black ink was also made by dissolving a common carbon substance. Gallnuts, growths found on oak trees, were often used toĬreate a dark, black ink. Scribes made ink fromĪ variety of materials. The shape of the quill point varied with the style of the Quill to a rough point, cut a slit to draw ink down, then trimmed the point Pens, called quills, were made from the feathers of a bird, which were soaked in water, dried, and hardened with heated sand.

The tools of a scribe, the person who copied Script was as important as the painting of the images. In a medieval manuscript often overshadow the words on the page. Were folded and nested, to make gatherings, usually

DONKEYS IN MEDIEVAL ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS SKIN

For smaller books, the skin was cut into two or more pieces. A big manuscript was assembled from sheets almost as large as a single skin. The whole, finished skin was then cut down to the size of the pages These steps made the surface receptive to inks and colors. First, the parchment was rubbed with pumice powder to roughen the surface, and then dusted with a sticky powder. Before parchment could be written on, it had to be specially prepared. The result was parchment, a smooth and durable material, that could last over a thousand years. On the stretching frame, while the skin dried. Parchment maker continually tightened the tension The process of scraping continued over the course of several days. A special, rounded knife was used to scrape the hide to the desired thickness. Soaked in fresh water, to remove the lime, and then stretched tightly on a frame. Scraped away the hair, and any remaining flesh. Skins were soaked in limewaterįor three to ten days, to loosen the animals' hair. The parchment maker selected skins of sheep, goats, or calves.

The transition from aįresh skin to a surface suitable for writing was a (gentle guitar music) - In the middle ages, parchment was used to

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)